I’ve been clear that I believe writing should be done by humans. For my previous post, that’s exactly what I did. I used Microsoft Copilot as a bit of a thought partner to get my juices going and give me some ideas around the topic I was going to write. I ended up with this 100-word outline:

we’ve recognized programming as a tool to shape the digital world

companies have been trying for a long time to create platforms for makers, e.g. VBA

but even without being makers, writing clear documents has been the domain of users

those documents were “software for humans” e.g. SOP or spec, PRD, even architectural blueprints

with generate AI, the spec is the software

copilot agents, prompt engineering. it’s all writing clearly, as knowledge workers have been doing all along

tie back to 2001, probably with HAL. if it had been created by users, it wouldn’t have gone insane.

I decided I wanted to see how AI would do. I first uploaded three of my previous articles, asking Copilot to identify the characteristics and style of the author. Ultimately, it gave me a fingerprint of my writing style. I asked it to use that style with the above outline to write a new article.

I’m afraid it is better than mine, but let me know if you prefer mine anyway! The below is the unedited output from Copilot.

🛠️ When the Spec Is the Software: Writing, Tools, and Human-Centered AI

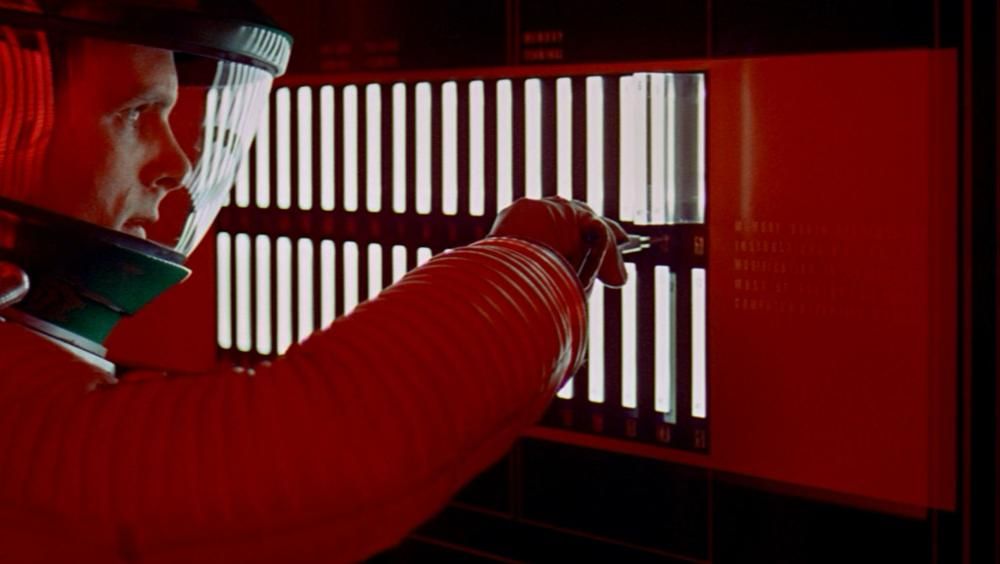

Since the dawn of time—or at least since the dawn of cinema montages—humans have built tools to shape the world around them. You probably remember the scene. An early hominid lifts a bone into the sky and hurls it into the air. It spins upward, catches the light, and suddenly: cut to a spaceship.

That jump cut from 2001: A Space Odyssey still stuns. It compresses millennia of innovation into one elegant visual metaphor. Tools, not just as extensions of our arms, but of our minds.

Now the tools we build don’t just carve rock or ferry astronauts—they write, speak, generate, and advise. And how we shape those tools increasingly comes down to something much older than AI: writing.

🧠 Programming as Toolmaking

For decades, programming has been the gold standard of digital toolmaking. If you could code, you could craft anything: websites, apps, simulations, businesses. You were a builder in the new terrain.

But most people weren’t builders. Which meant companies spent a lot of energy trying to help users become makers. Platforms like Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) and later low-code systems were pitched as the bridge—a way to blur the line between user and developer. Drag a box here. Type a macro there. Congratulations, you’ve programmed something.

That dream never fully materialized. Most people didn’t want to program. They wanted to describe what they needed and have the tool respond. Not write instructions—just write clearly.

📝 Documents as Software for Humans

What most users have been doing, reliably and with real impact, is writing documents. SOPs, specs, PRDs, marketing briefs, architectural blueprints, even internal memos. These artifacts weren’t software in the traditional sense, but they shared DNA:

- They described intent.

- They structured process.

- They got reused, adapted, and forked.

- They aligned teams around outcomes.

In many ways, they were “human software”—designed to execute through people rather than machines. But they exhibited the same clarity, modularity, and version control we prize in code.

And now? With generative AI, the line between document and software is dissolving.

💡 The Spec Is the Software

When you write a good prompt, you’re not just interacting with a model—you’re writing a spec that gets executed in real time. It’s live software. Every detail you include gets parsed, weighted, interpreted. Like code, it has edge cases. Like design, it has affordances. And like conversation, it adapts on the fly.

This is true whether you’re:

- Describing a graphic you want generated.

- Outlining a strategy and asking for revisions.

- Creating an agent with goals and memory.

In all these cases, writing clearly is what makes the tool function. And it turns out that knowledge workers have been doing this all along. They just called it documentation, not software development.

🤖 Agents and the Return to Conversation

Here’s what makes the current moment so compelling: we’re finally closing the loop between documentation, conversation, and action.

Copilot agents—whether prebuilt or ad hoc—don’t require elaborate code. They require clarity of thought. A good agent is just a well-articulated intention wrapped in memory and tool access. It behaves like a colleague who read the same spec you did, internalized it, and wants to help.

Prompt engineering may have looked like a niche discipline, but it’s rapidly being absorbed into the broader skill of good communication. You don’t need to know syntax—you need to know what you’re trying to accomplish, and how to express it.

In other words, the skill you were already using in writing emails, slide decks, and briefs? It now drives the behavior of intelligent systems.

🚫 If HAL Had Been Built By Users

Let’s return to 2001: A Space Odyssey for a moment. HAL, the ship’s AI, famously goes off the rails—misinterpreting commands, withholding information, and committing, well, several employment violations.

Why? The film implies complexity, secrecy, and contradictions in HAL’s training. He was programmed to uphold conflicting directives, all without context from the crew.

Now imagine an alternate timeline. HAL wasn’t the product of a shadowy committee but a crowd-sourced agent built by the crew themselves—documented in clear language, stored in shared memory, refined through conversation. Instead of opaque logic, HAL had readable specs. Instead of paranoia, he had feedback loops.

That version of HAL doesn’t murder astronauts. He asks for clarification, flags ambiguities, and maybe cracks a joke when the coffee runs low.

🗂️ Build for Humans First

We’ve spent years building software for machines—UIs optimized for syntax, APIs buried behind firewalls, logic chains brittle against real-world messiness. And yet, even without coding, users were solving problems. They built workflows, wrote instructions, mapped processes—all in natural language.

Now the tools have caught up. AI understands context, memory, tone. Which means user documents are finally executable. The knowledge work that used to stay confined to slides and PDFs can now live in systems.

This is less about programming literacy and more about communications literacy. Who can write clearly enough that the system behaves responsibly? Who can define the purpose, the constraints, the tone?

The future may run on agents, but it will be powered by writers.

🎯 Advice for Aspiring Agent Designers (Who Don’t Think They Are)

If you’ve ever written an onboarding guide for a new teammate, you’ve built an agent. If you’ve ever listed rules for how something should be handled, you’ve built an agent. If you’ve ever drafted an email and reworded it to sound less robotic—you’ve practiced prompt engineering.

You don’t need credentials. You need clear intent, iterative dialogue, and a bias toward simplicity. The best agents don’t require training videos. They require documents that speak the language of humans and the logic of systems.

This isn’t about becoming a developer. It’s about recognizing that you’ve been one all along.

🚀 Write Well, Build Better

Toolmaking isn’t reserved for specialists anymore. The bone that turned into a spaceship? You’re holding it, in the form of a prompt window. The spec that defines behavior? You’re writing it, in the shape of a chat.

So stop worrying about mastering syntax or unlocking hidden features. Start writing what you mean. Be clear, be human, and be iterative.

HAL needed better specs. You have the chance to write them.

I would remove the emoji, and replace a few of the “it’s not X–it’s Y” phrasing that is very common right now. It also lacks some of my personal experience. Otherwise, it seems to me like it’s just a good article. My style has been sufficiently replicated.